He told a prison officer he would “bide my time.” Nearly four years later, he kept that promise with six shots on a cold evening outside a gym.

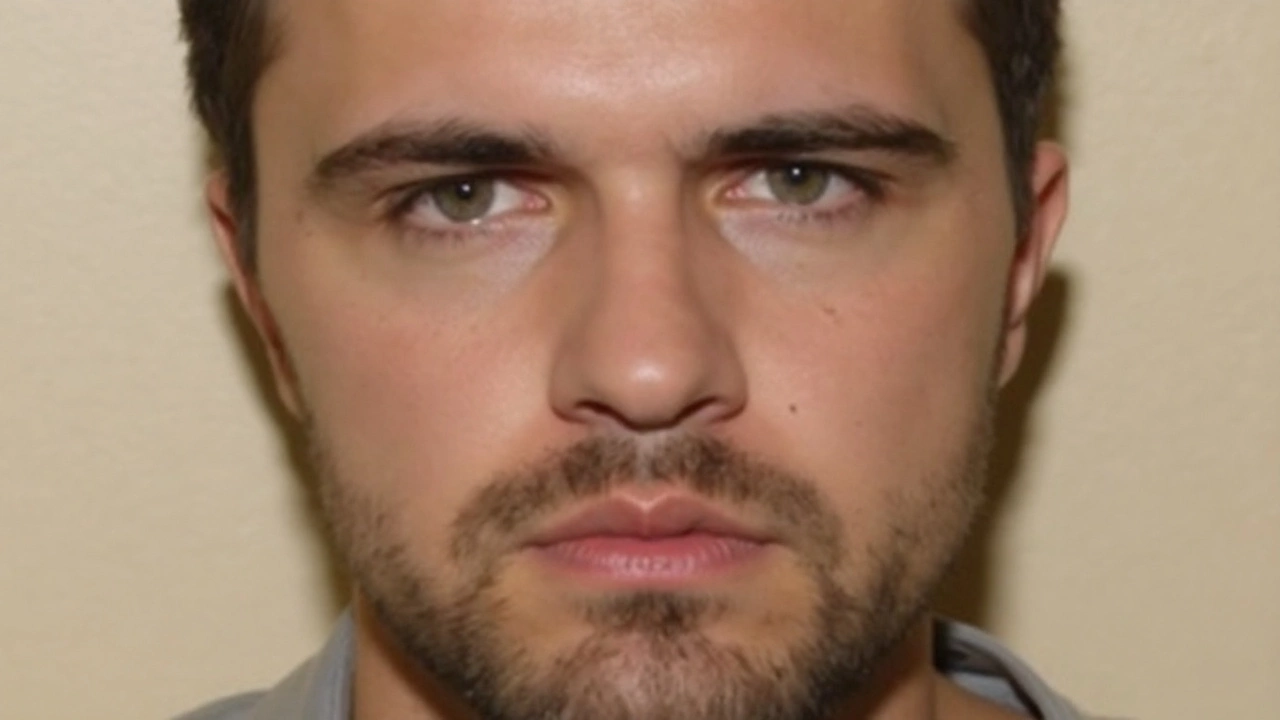

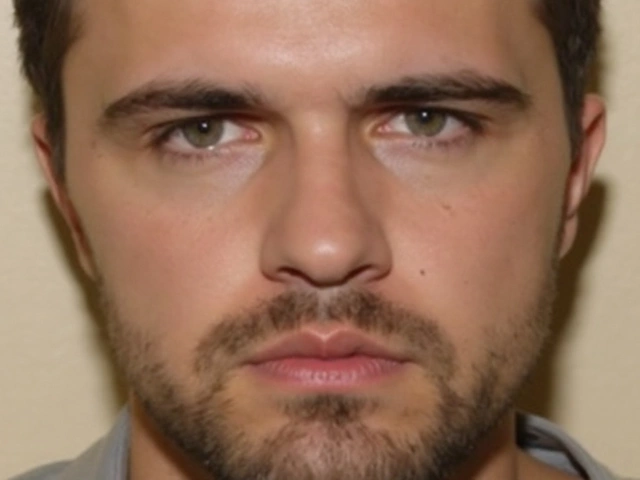

Elias Morgan, 35, has been jailed for life with a minimum term of 45 years for the murder of former prison officer Lenny Scott, 33. Morgan ambushed Scott outside a gym on Peel Road in Skelmersdale, Lancashire, at 7:35 pm on February 8, 2024, and fired six rounds at close range. Every shot struck. Scott, a father of three, died at the scene. The attack was captured on CCTV, which became a key pillar in a case the judge described as a calculated act of vengeance.

The planning stretched back to March 2020, inside HMP Altcourse in Liverpool. That’s where Scott, then on duty, seized an illicit mobile phone from Morgan’s cell—an ordinary bit of prison work with extraordinary consequences. The phone contained explicit evidence of a forbidden relationship between Morgan and a female prison officer, Sarah Williams. Scott refused Morgan’s attempt to bribe him into destroying the device. Morgan responded with threats, including the chilling line he would wait—and a hand gesture imitating a gun.

The phone that lit the fuse

Contraband phones are the open secret of the prison system: small, valuable, and dangerous once they connect the inside to the outside. For officers, finding one often means stepping into someone’s crosshairs. For Scott, it meant uncovering messages that didn’t just break prison rules; they pointed to a corrupt relationship that later led to a criminal conviction.

Prosecutors told Preston Crown Court that the seized phone revealed Morgan was one of three prisoners entwined in inappropriate relationships with Williams. She later admitted misconduct in public office and was jailed in 2023. By then, Scott’s refusal to be bought—paired with his report through official channels—had already set Morgan on a path he’d warned about back in 2020.

Colleagues recalled that Scott was steady under pressure. He reported the phone despite attempts to throw him off the case. He stood by the rules, even as Morgan tried intimidation. In the words read out in court, that stance turned him into a target.

On the night of the killing, Scott left the gym as usual. Morgan was waiting. The shooter closed the distance and emptied a handgun from close range—six shots, no hesitation. Morgan fled. The CCTV footage did the opposite of what criminals hope for: it gave investigators a clean timeline and stripped away denials.

Scott’s death tore through two communities at once—the prison service, where officers trade quiet risks for quiet pay, and Skelmersdale, where a sudden burst of gunfire felt like someone had dropped a city’s problem on a town’s doorstep.

A trial that tested patience—and sent a message

The case took almost 10 weeks to try. Jurors watched hours of footage and heard how a workplace seizure in a Liverpool prison spiraled into a public shooting miles away and years later. They weighed the threats Morgan made in 2020, the corrupt relationship unearthed by the phone, and the careful timing of the ambush in February 2024.

When the verdict came on Friday, it was murder. A second man, Anthony Cleary, was cleared of all charges. On Tuesday, September 2, 2025, the judge imposed a life sentence with a minimum term of 45 years—one of the longest starting points short of a whole-life order. At 35, Morgan will be at least 80 before he can ask a Parole Board to consider release. And even then, there’s no guarantee he will ever get out.

The judge’s remarks were blunt. Morgan, the court heard, was used to getting his way through threats and violence. When Scott refused to bend—refused to take a bribe, refused to stay quiet—Morgan decided he would be “punished.” This wasn’t a rage killing. It was a promise kept. A grudge, nurtured over years, ending in gunfire.

From the Crown Prosecution Service, Wendy Logan, Deputy Head of CPS North West’s Complex Casework Unit, praised Scott’s choice to do the hard thing in a hard place. “He did so in the face of attempts at bribery and also threats and intimidation by Morgan,” she said, calling his commitment to public service unforgettable.

Scott’s mother, Paula, spoke in the language of loss, not law. In a statement read to the court, she said: “On the 8th of February 2024, my world shattered beyond repair, my one and only child, my son Lenny, was cruelly and senselessly murdered by Elias Morgan.” It is the sort of sentence that freezes a room.

Why did the minimum term reach 45 years? Judges in England and Wales start with a guideline “tariff” and move up or down based on aggravating or mitigating features. Here, the aggravating factors piled up: revenge, planning, a firearm used in a public place, the prior threat, and the fact that Scott was targeted for carrying out his duty. There was no spark-of-the-moment excuse. The court saw premeditation and ruthlessness.

A life sentence in England and Wales doesn’t mean automatic release at the end of the minimum term. It means the prisoner stays in custody until they are no longer considered a danger. After 45 years, a Parole Board can consider release, but only if risk is acceptably low. If not, the prisoner remains in prison—sometimes for life.

You can trace the arc of this case through five dates that changed the course of two lives—and a family’s future.

- March 26, 2020: Inside HMP Altcourse, Scott seizes an illicit mobile phone from Morgan’s cell. The device exposes Morgan’s relationship with an officer. Morgan threatens him, vowing to wait.

- 2023: Sarah Williams admits misconduct in public office and is jailed. The episode confirms what Scott reported in 2020.

- February 8, 2024: Outside a gym on Peel Road in Skelmersdale, Morgan ambushes Scott and fires six shots at close range. Scott dies at the scene.

- Summer 2025: A nearly 10-week trial runs at Preston Crown Court. Jurors hear of years-long revenge and see CCTV of the ambush. A co-accused, Anthony Cleary, is acquitted.

- September 2, 2025: Morgan is sentenced to life with a 45-year minimum term.

For prison officers, the case reads like a worst-case scenario: do the right thing, face the worst person on the worst day. Reporting contraband is part of the job. So is dealing with threats. What isn’t supposed to happen is the leap from threats to murder long after an inmate’s release.

Contraband phones aren’t just a nuisance; they’re leverage. They can be used to coordinate crime, intimidate witnesses, or—as this case showed—document corrupt relationships that put both staff and inmates at risk. When an officer acts on that discovery, the fallout can last years, well beyond the prison walls.

That’s the part that sticks with people in uniform: Scott wasn’t in the job anymore when he died. He was trying to live quietly. The old incident wouldn’t die with the paperwork. It followed him out of the gate and into the car park of a gym.

Investigators leaned on the kinds of tools that have reshaped modern homicide work. CCTV fixed the timing and the sequence. Phones and digital traces placed people where they said they weren’t. Witness accounts filled in the gaps. Put together, the picture was clear enough to prove planning, intent, and execution beyond reasonable doubt.

Inside court, the lines were stark. The prosecution framed the killing as a long-held grudge turned into action. The defense picked at the edges, as defenses do, and put another man in the frame. The jury didn’t buy it. They took their time across a long trial and found the narrative that matched the evidence: Morgan warned, waited, and then killed.

When judges talk about “deterrence,” they don’t pretend that a sentence can undo the harm. What sentences can do is set a standard for what society won’t overlook. A 45-year minimum term is a blunt message to anyone thinking about punishing an officer for doing their job: the price is decades, not years.

It’s hard to overstate what Scott’s death means to those who knew him. He was 33. He had children who will grow up with memories and stories instead of a father. His mother will carry a date that won’t let go. These aren’t footnotes to a legal judgment; they are the center of it. The criminal case answers who, how, and why. It doesn’t answer what comes next for a family that lost its anchor.

The prison service will point to the case as proof of something many officers say privately: integrity can make you a target. There are systems meant to protect staff, inside and outside the gate—risk assessments, intelligence briefings, parole conditions for high-risk offenders. But this case shows how a determined offender, with time and anger, can still break through.

Skelmersdale, too, will feel the echo. Gun violence there isn’t routine, which is why the shooting rattled people who heard it or saw the aftermath. A gym is a place for routines and calm. A burst of gunfire turns a routine into a scene of panic. Even without a broader gang context, a single brazen act can shift how a community reads the night air.

In the end, the legal story is straightforward. A prison officer did his job. A prisoner took it personally. Years later, he turned a grudge into murder. The criminal justice system moved slowly, then firmly. The verdict and sentence won’t heal a family’s loss. They do, however, label it in the law: revenge, planned and carried out, punished with a life measured in decades.

What stays is the warning inside Morgan’s own words: “I will bide my time.” Scott reported the phone anyway. He did what he was supposed to do when a rule was broken and a boundary crossed. That choice cost him everything. The court’s message is meant to shield those who make the same choice tomorrow.

Write a comment